“YOU ARE ALL TRAITORS, SPIES AND SABOTEURS” |

"The people went out to look at us:" The Fascists are being brought "." A brief history of ethnic Germans in the gulag: from the beginning of a mass expulsion in August 1941 to the lifting of the “special settlement restriction” in December 1955.

Mediason and Deutsche Welle publish the second of Elena Shmaraeva’s essays about the history of Russian Germans - from the start of a mass expulsion in August 1941 to the lifting of the “special settlement restriction” in December 1955.

Part 1: Shot "on a common basis". A brief history of ethnic Germans in the gulag

“In the summer of 1941, we harvested wheat, lived in trailers. I remember well that they told us that they were sending us out, and that we had to urgently get ready for the journey. <...> We arrived home, where my father cuts a pig and a lamb. He wanted to cut the ducks, but they swam away to the middle of the lake, ”the schoolgirl Amalia Danielia from the German village of Polevodino in the Saratov region remembered on August 28, 1941.

Friede Koller from the Saratov village of Messer was six years old: “When a decree was announced in our village, my father did not believe in it. "It cannot be that a great many people are removed from their native places and resettled inland." In the morning, all the villagers had to gather at the church to get off on a long journey. Until the night in the village there was a terrible cry and cry. "

“I remember they came to our house and announced this decree. The deadline for the training camp was three days, ”Alvine Hof in August 1941 was five years old, her family lived in the Volga Republic Germans in the village of Dobrinka.

Without noise and panic in cattle cars

The “decree” mentioned in the stories of the Germans of the Volga region and the Saratov region is the order of the NKVD No. 001158 signed by Commissar of Internal Affairs Lavrenti Beria. From this document, entitled “On the arrangements for the resettlement of Germans from the Republic of the Volga Germans, Saratov and Stalingrad Regions”, dated August 27, 1941, mass deportations of tens and hundreds of thousands of people, of entire nationalities, mainly to Kazakhstan, Siberia and the Middle Asia

For the implementation of the order, 12,500 soldiers and officers from the NKVD troops were sent to the listed areas. The Chekists, reading the document, warned that the heads of families that had refused to evict would be arrested, and their families repressed. It was prescribed to act "without noise and panic." The operation was headed by the deputy head of the USSR interior affairs department Ivan Serov and the head of the gulag Viktor Nasedkin in the Volga region. Less than three weeks were allocated for eviction: “The operation should begin on September 3 and end on September 20 of this year.”

The evicted Germans were given from one to three days for gathering, allowed to take 12-16 kilograms of things and food with them, and people — who were on carts, who were on barges, who were walking — accompanied by soldiers were sent to the nearest railway stations. They tried to escape and were caught and under escort led to the train. Before boarding the train, all Germans entered a line directly in their passport that they could only live in certain areas of Kazakhstan: “The revealed people of German nationality have the police announced that they are obliged to travel to the Kazakh SSR, and write in the passport that the passport holder has the right of residence only in the areas listed by order of the NKVD of the USSR. Thus, the Germans will be forced to go to the indicated places, because with such a record in the passport they will not register it anywhere else in the city ”,

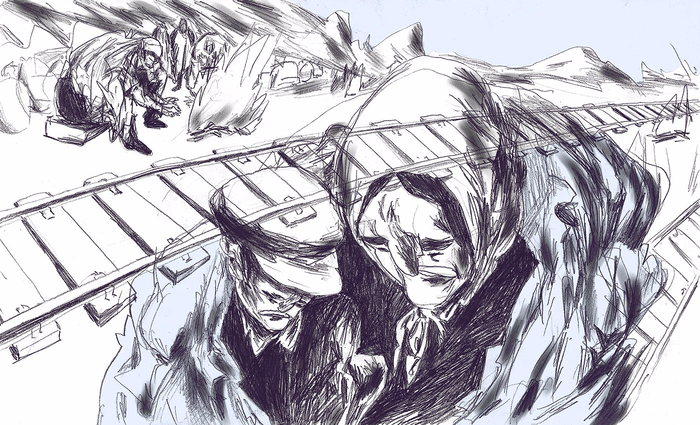

“For two days we waited at the station until the cars were served. Carriages arrived in which coal is transported, ”Alvina Hof told. “At first, people were forced to clean the cars from manure, then they were loaded into these cars,” Maria Alva recalled. “They loaded us into cattle cars - there was nothing in them, no shelves. People lay on the wooden floor. The men made a hole in the floor to go to the toilet. On the way, we did not feed, everyone ate household supplies, ”shared Amelia Daniel with similar memories.

Following the Volga Germans, resettlement orders were heard and read in local newspapers by Germans in the Leningrad Region, Moscow and the Moscow Region, Crimea, Krasnodar Territory, Ordzhonikidze Territory (now Stavropol), Voronezh, Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), Tula Region, Kabardino-Balkaria, North Ossetia, Zaporozhye, Stalin and Voroshilovgrad (now - Donetsk and Lugansk) regions. Also the Germans of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia were subject to resettlement. Operations were carried out hastily, thousands of soldiers and officers were thrown at each.

3.

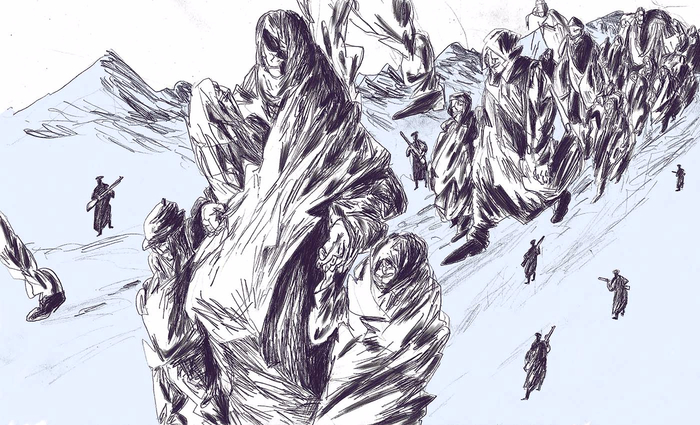

Image: Vlad Milushkin / Mediazona

V subject: “National Changes” in the service of the USSR: national problems in the Red Army

"There were separate counter-revolutionary attacks by anti-Soviet-minded individuals and attempts by some Germans who were to be resettled - to the destruction of their livestock," the UNKVD of the Krasnodar Territory reported to Moscow. “The German Geller, candidate of the CPSU (b), after the announcement of the relocation, came to the secretary of the city committee of the CPSU (b), leaving his candidate card, and said:“ Why do you scoff at us, humiliate honest people, I will not go, shoot me ”” - Commissar of the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic Stepan Filatov reported. But more often the reports “upstairs” were the same as that sent by the people's commissar of Kalmykia Grigory Goncharov on December 22, 1941: “During the eviction of people of German nationality ... <...> there were no negative moods, no incidents, excesses, escapes, also refusals from eviction among the evicted did not happen. "

During the first two months of deportation, mainly from the Volga regions, more than 400 thousand Germans were taken out. Viktor Zemskov, author of the book “Special Settlers in the USSR, 1930–1960”, cites data on the deportation of about 950,000 Germans during the war years.

"We should have no mercy to the Germans"

The local population is satisfied with the actions of the government to evict the Germans and considers them to be correct, reported the heads of operations in the Volga region, the Kuban and the Caucasus. "Now I will quietly go to the front, knowing that my family is safe from the internal enemy," said Serov Deputy Commissar Serov of a certain worker from the city of Engels. He also reported on denunciations of the disgruntled: "A bacteriological laboratory worker L. said that in a conversation with her, some Wulf said in a threatening tone that if the Germans were resettled, they would open an internal war and not the same as at the front."

People's Commissar of Kabardino-Balkaria Filatov quoted in a memorandum statements satisfied with the deportation of minor republican officials and employees. “It’s good that the Germans are being resettled, it’s high time, there are many spies among them. The Germans at the front are mocking our fighters and local residents, ”said an employee of the People's Commissariat of National Security of the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic named after Chirikin. “The decision to relocate the Germans is absolutely correct, we should have no mercy towards the Germans. The Germans are dishonest, insidious, they can not be trusted, ”the employee of the republican Narkomfin Beytokov agreed.

There were also cases of deportation on the initiative “from the field”: the State Archive contains a memorandum on the “activation of the counterrevolutionary activities of the Germans” in the Kuibyshev region (now Samarskaya) with a proposal to evict 1,670 German families to Kazakhstan (more than seven thousand people, almost half of they are children).

To the places of reference, crowded wagons for livestock and cargo went for weeks. “The train went more than a month ... <...> On the way, people were very cold, it was the beginning of winter, the train was going to Western Siberia,” says Maria Alva’s memoirs. Frida Bechtgold's family and fellow villagers from the village of Old Leza in the Crimea were brought first to the Caucasus, then to the Moscow region, and from there to Kazakhstan: “They brought us to the Makinka station of the Akmola region”. “We went from Saratov to Omsk for a whole month. Many had a stomach ache, a dysentery epidemic was on the train. Several people died, the corpses were left at the stations. Our family was lucky, we sat on the bunks on the second floor, bent over, but we had our own pot taken from the house. I also had dysentery. <...> In the evening we arrived at the station of Kolonia, Omsk Region. There was snow all around, ”Alvina Hof recalled.

“On October 9 of this year, 14 echelons were sent, in which 8,997 families were loaded, with a total of Germans 35,133 people. Only one train has not been shipped from the Novo-Kuban operational section, as the loading of the Germans recorded in this section is delayed due to the lack of railcars, ”the memorandum of the head of the Krasnodar regional operative for the resettlement of Germans Ivan Tkachenko reads. One echelon is from two to three thousand people. While waiting for the cars at the station, they burned fires, prepared food from the supplies captured from the house, slept on bare ground. In Kalmykia, the republican people's commissar Goncharov wrote, because of the November rains and mudslides, the trucks and carts, on which the Germans had to drive to the stations, got out of order and got stuck in the way. For 19 days, “persons of German nationality” waited for loading into trains: in the rain, in the mud, without a roof over your head. At the Abganerovo station, the wagons filled with people for two days stood without moving, as there were not enough locomotives to send.

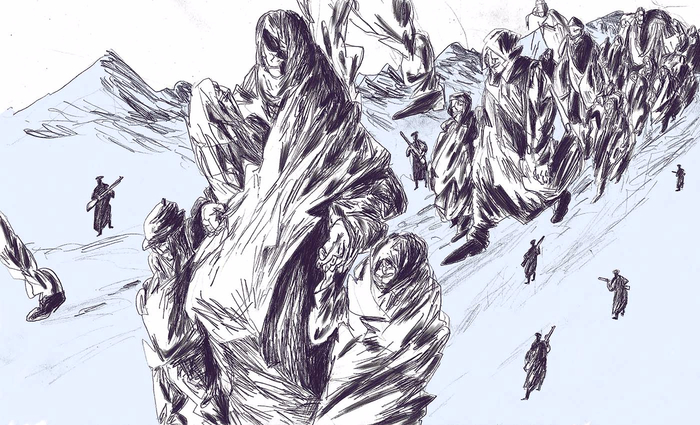

The evicted Germans arrived in Siberia and Kazakhstan in late autumn or in December. “On November 1, they came to Siberia to Kerzhaks, these are Old Believers from Siberia. <...> The village was small: only twenty houses and an office. Old Believers, harsh people, they didn’t take us to their homes, they didn’t let anyone in, we lived in an office. Old-timers were surprised, we thought the Germans were with horns, and we are just as normal people as they are, ”Frida Koller shared her first impressions of the place of exile. “The dirt was terrible, the carts were also dirty, we barely moved. Thirty kilometers traveled almost a day. When we drove through villages and villages, the people went to look at us: "The Fascists are being taken." We were children and we didn’t really worry about it, but our parents were very hard, ”Valdemar Merz was six years old,

The family of Kristina Bishel (then she was 14 years old) who was exiled from the Krasnodar Territory was more fortunate - they did not meet the aggression of the local people: “<...> We were brought to Kazakhstan, to the Shcherbakty station. Unloaded into a terrible cold and numb, the hungry were taken to the villages. We got (the whole family) in the village of Aleksandrovka. The chairman of the village council Sologub met us and took us to his home. He had two children, and his daughter's wedding had already been appointed, but he postponed the wedding. He was a very kind person. Never sat at a table without us. He tried to give us some things, because we were almost naked. And the people in the village treated us kindly. ”

“We arrived in Kazakhstan. There is plenty of snow. Dismantled us in the Kazakh houses. Kazakhs do not understand a word either in Russian or in German, and we do not speak a word in Kazakh. And with us was our grandmother Liza, she understood a little Tatar. Kazakh and Tatar languages are our own - this is what grandma translated to us. In this village we ate bread while the older brothers worked. For the day they were given bread cakes. They brought her home and we shared a cake. There was little work, and there was no bread without work, ”said Frida Lauer, whose family was moved from the Crimean farm Nurali. Soon her elder brothers, like most German special settlers, found work at a local collective farm. However, they did not work there for long - they were mobilized into the so-called labor army.

4.

Image: Vlad Milushkin / Mediason

In topic: How to kill the "red" Russia. The death penalty procedure in the 1920s – 1930s. Part 4

Through the military registration and enlistment office

“The Gulag finally collapsed to get into the army at the Novocherkassk military registration and enlistment office, in Akmola region, where we were evicted in the snow in the autumn of 1941 and from where they sent us at the end of January 42, and on “labor mobilization”. <...> Yes, I dreamed of the Red Army, but I was sent to a concentration camp, as an enemy of the Soviet government or a criminal! <...> Yes, and “planted” something like that! Through the military enlistment office, according to a uniform agenda: “with a mug, a spoon, a ten-day supply of food,” as if they were really called to the front, ”Gerhard Voltaire, who passed through the Bakalstroi camp in the Chelyabinsk region, wrote in his book.

He was 18 years old when, in January 1942, a completely secret Resolution of the State Defense Committee No. 1123 was issued on the mobilization of German men from 17 to 50 years old in the “working columns”. The document prescribed to oblige 120,000 people to appear at the military registration and enlistment offices at the place of residence and transfer them to the NKVD for work on logging, building factories and railways. On January 12, 1942, order No. 0083 was issued, signed by Commissar Beria, in which it was stated that the "immobilized" would be accommodated in special camps at the camps of the NKVD, and they were supplied with food according to the norms of the GULAG. Mobilized to the workers' columns were instructed to fulfill and overfulfill the production plan, and the operational-KGB department - to stop in advance “any attempts to disintegrate discipline, sabotage and desertion”.

Voltaire and other Germans driven to Bakalstroy built a metallurgical plant with a mining industry, which was later planned to smelt steel for tank armor. “We started from the first excavations for the barracks and from the pits under the poles for wire obstacles. Around themselves. Not far from each of the future key facilities - Domenstroi, Stalprokatstroya, Koksokhimstroy, Zhilstroi and other equally important points of a huge construction site - were laid down camps so as not to escort the strictly guarded German “special contingent”. In turn, this whole machine had an external fence about 30 kilometers long and armed guards so that not a single "hard-mobilized" person could escape from the gigantic camp. "

Labor mobilization was continued by the orders of the State Defense Committee No. 1281 of February 14, 1942 - it extended to more territories from which the Germans were called up - and No. 2383, which extended the call to the labor army for teenagers from 15 years and men to 55 years, in addition were subject to mobilization of women from 16 to 45 years. Since women with children up to three years old and pregnant women were not taken away, very young girls and women over 40 years old were in the camps.

“In January 1942, all men of German nationality from seventeen to fifty years old were taken to the labor army in the Sverdlovsk region for logging. This fate has not bypassed our father. ” “In 1942, mother and her sister Amalia were taken to the labor army in the Ural city of Chelyabinsk. There at the brick factory she worked as a hawker, rolling out carts for bricks. Amalia worked there too. ” “In 1942, as a new year, I was taken to the labor army in the city of Kansk, Krasnoyarsk Territory. I first worked on the sawmill, sawed logs, then dragged sleepers. ”

“In the fall, my father was taken to the labor army in Chelyabinsk, me in the winter of 1941 to the labor army in the Sverdlovsk region, and my brother to Kartsk in the labor army to the mine.” “Father was sent to the labor army in the city of Krivoshchekovo, Novosibirsk region”. “Father together with brother Friedrich were taken to the labor army in the Perm Region to the Chardyn forest area. My father did not send us any news, he was gone. ” In the collection of memoirs of the Russian Germans “Bitter Fate”, recorded by Anna Schaf, there is not a single story in which the labor army is not mentioned.

In the subject: “Fingers door smiled. Needles and blades popped under nails ”

“In February 1943, his elder brother Kolya was seventeen years old, and he was taken to the labor army in the city of Orenburg. There have been severe cold in winter. Kohl worked in the mine, the clothes were not warm, he caught a cold, fell ill, could not leave the mine to the surface. The comrades carried his bread down to the pit, where he lived without seeing the white light.

He was starved and weak, fell ill with pneumonia. In order not to die, the brother decided to escape from the mine, but he was caught and put in a prison camp. Our Kolya returned from there only in 1948 to a patient with tuberculosis, weakened from poor nutrition. ” “In 1943, my mother was taken to Omsk to a military factory, but my mother was hard there and a month later she ran away from there. In the evening she came, and at night they already knocked at the house, they took her away. At this time, all women who did not have babies were taken to the labor army. <...> Many women cried, screamed and were not given to the escort. Such people were tied to wads with ropes and carried by force to wagons. ”

"Trudmobilizovannye", as they were called in the official documents of the NKVD, worked in the camps of Siberia and the Urals: on construction sites, logging, in mines, in oil production. Ivdellag, Usollag, Tagillag, Bakalstroy, camps in the Chkalov region (now - Orenburg), Bashkiria, Udmurtia. According to the data cited in his article by the Chelyabinsk historian Gregory Malamud, in the Urals by January 1944 there were more than 119 thousand Germans who were mobilized, which was about a third of their total number in the USSR.

Not all Germans mobilized in this way were placed at the disposal of the NKVD. Historian Arkady Herman writes that about 182 thousand Germans who were labor-mobilized during the war years worked at NKVD facilities, and about 133 thousand more at facilities of other people's commissariats (coal and oil industry, people's commissariat of ammunition).

“You are all traitors, spies and saboteurs”

The author of the “Complete Rest Zone” Voltaire writes that they, mobilized by young Komsomol members and yesterday’s schoolchildren, at first even made it difficult to write in the questionnaire special features like bulging ears or a crooked nose, and towers and barbed wire neither did they suggest that they could be locked up like prisoners. Especially in the official address they were called "workworn-mobilized comrades" and appealed to the "patriotic duty of the Soviet people" to work in the name of victory over the enemy: "It was already thought that our place in the common struggle against the fascist invaders was satisfied. The feeling of a clear conscience soothed, tuned in for hard work, gave strength to overcome future difficulties. ”

But the illusions about voluntary, conscious labor quickly dissipated: instead of “comrades,” Fritz and Fascists sounded in circulation; they fined the plan for not fulfilling the plan, reducing bread from 750 grams to 400 grams. “On the same day, guards appeared on the towers and on the watch, and behind the camp gates we were met by an armed convoy with a constant insulting shout:“ Step to the left, step to the right - shoot without warning! ””.

5.

Image: Vlad Milushkin / Mediason

Bruno Schulmeister, who was mobilized in Kraslag, recalled how, on the first day of their squad's arrival at logging, the chief engineer greeted the replenishment in the following way: “Dear work-mobilized comrades! You came here to earn big money, help your families, prepare timber for the front, cut sleepers and boards at timber mills ... ”The next morning, when the“ comrades ”did not quickly build up for the morning calibration, the same engineer yelled:“ A-aa , fascists, you are waiting for Hitler! Do not want to work? We will teach you - quickly forget Hitler! ”

“The next morning, after arrival, we were taken up into an utterly early hour and lined up in a column six people each. We were addressed by an important colonel named Pappertan. <...> He literally stated the following: “You are all traitors, spies and saboteurs. You should have been shot to death from a machine gun. But Soviet power is humane. You can redeem your guilt by conscientious work, ”Reinhold Daines recalled his arrival at the construction of the Theological Aluminum Plant (Bazstroi NKVD). “You were brought here to wash away your shame. Who are you, you already said. So only labor can save you from deserved punishment. And remember: not one has left here yet - everyone is lying on the hill! .. ”the head of the 16th Ivdellaga camp welcomed the newcomers,

After Ilya Ehrenburg's article “Kill the German!”, Published in the summer of 1942, Bazstroi’s leadership didn’t find anything better than hanging a banner with this slogan right on the gates of the 14th construction detachment, where the Germans lived mobilized, told Reinhold Deines. Alexander Muntaniol, who was mobilized to Solikamsk, recalled about the slogan “Do you want to live - kill the German!” In the detachment canteen for the Germans.

Theodor Herzen, who worked at logging sites in the Sverdlovsk region, told how labor-mobilized Germans had to fight local people (also special settlers sent to the Urals after dispossession) for the right to go to work by train - they did not want to let the “fascists” into the cars. The children's cries of “The Germans are being led!” - and the spitting in the back is remembered by the workers of the labor army, who had to go to the construction site or to the mines through the settlements.

Among the memories of Alexander Muntanyol, there is another example of relations with residents: “At the end of the summer, our penal team was sent to maintain in good condition the road along which the vegetables were taken out of the Gulag sub-farm. We lived in the village, in the house where the school was located. At first, the local people avoided us, and we understood the reason: in the village there was a man in the form of internal troops. It was he who worked the inhabitants so that they would not communicate with us.

But life went according to its own laws, and, no matter how hard the KGB tried to keep people in the blinders, this was not always possible. Soon the villagers got to know us better, and when they heard that we spoke Russian, we no longer shy away from it. In the evenings, the school had fun. From local girls there was no end. Women also came - “to smell the masculine spirit”, as they said. Having lived in the village for about two months, we really became friends with its inhabitants. Our guys helped clean up the yard, chop firewood for the winter, repair the fence, etc. When they left, the whole village left us to escort, people sincerely wished us well. ”

In the subject: “They say from the financial department of the KGB. We owe a favor. You still owed for the teeth "

Death or term

The power of the hard-mobilized was in direct proportion to the norms of production and did not differ from the rest of the camps of the Gulag - such a system was called the “pit”. In 1942, the gradation of these norms changed several times in the direction of reducing the ration, and by December, 700 grams of bread was supposed to produce a standard, and 800 grams - to produce 125% of the norm. Over 80-90% of the norm produced 600 grams of bread, less than 80% - 500 grams. Those who could not cope with half, received 400 grams of bread, simulators and penalty box - 300 grams. In the hospital barracks, one could count on 550 grams of bread.

“Kotlovka, especially in the conditions of the low nutritional standards of 1942-1943, left the prisoners with a very little chance of survival for the Gulag. The minimum guaranteed rate, as shown by the prisoners of Tagillag, meant a slow death from dystrophy. At the same time, camp wisdom stated that “a large ration kills, not a small one,” since the fulfillment of the norms by 150% entailed a loss of strength, not compensated by an increased non-nutritive ration, ”writes the historian Malamud in the article“ Mobilized Soviet Germans in the Urals in the years 1942-1948. He notes that, in reality, rations were even lower than expected: there are numerous inspection reports that revealed the issuance of bread intended for labor-intensive workers, the camp management, the staff, the accounting department, and other civilian employees.

“With such a poor diet, I had to go to the toilet only twice a week. Hunger brought my friend to the point that when he, after a long search, could not find anything and saw a recovering cook in the toilet, he asked me: "Fritz, what do you think ... can I try it?" - "And do not dare to think!" - was my answer.

Sick horses, sick horses, as well as cats and dogs, even looked for rats, everything was devoured. The starving people looked atrocious, ”Friedrich Loures wrote in his memoirs“ Life in Timscher and other hard labor camps of Usolllag ”. Bruno Schulmeister recalled how in Kraslag in the winter of 1942-1943 they stopped giving out bread, instead of it they were fed frozen potato and cereal from whole grains of wheat that the stomach did not digest.

Gerhard Voltaire in his book on the labor army mentions two cases of cannibalism, which former prisoners of labor camps told him in letters. Waldemar Fitzler wrote about a murder committed by fellow freaks with the aim of cannibalism. Andrei Bel, who was serving labor service in Usollag, told about the death of one of those mobilized in logging. “It was established that the members of the brigade should deliver the body to the watch. Otherwise, the latter in incomplete composition was not allowed in the “zone”.

It was important for Enkawedeshnikov to establish that none of the German "socially dangerous contingent" had escaped ... <...> I did not want to drag a heavy burden on myself to any tired people. On this basis, a monstrous thought was born in the minds disfigured by hunger - to profit from the insides of a corpse. With "plausible" goals: to ease the burden and at the same time gain strength to deliver the body to the watch. The letter does not indicate what the consequences of this blatant plan were. But it is said that the "saving" idea was realized. "

6.

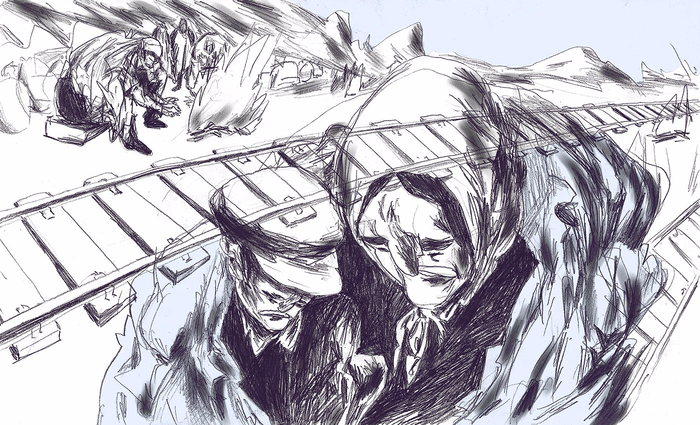

Image: Vlad Milushkin / Mediason

“Death attacked us with all its strength,” wrote Leopold Kinzel, who worked at the Talits camp in Sverdlovsk Ivdellag. - In the zone they walked, crawled slightly living corpses, utterly emaciated, emaciated, with swollen legs and bulging eyes. By the end of the working day, the camp commander sent a carriage coming from the forest to meet him. Fully exhausted put on her and taken to the "zone". Every day 10-12 people died. The chief did not regret them, but was unhappy that, taking into account the dead, he was not reduced to a plan for logging. In the neighboring camp there was the same situation, and the chief Stepanov spoke directly before the line: "As long as I am the boss here, none of you will come out alive here." Indeed, by July 1942 only half of the 840 people in the camp remained. ”

According to historian Arkady Herman, in 1942, 11,874 labor soldiers died in the camps of the NKVD - more than 10% of all those mobilized. In some camps, these figures were much higher than average: in Sevzdorlag and Solikamlag in 1942, every fifth labor-mobilized died, 17.9% of Germans who worked there died in Tavdinlag, and 17.2% in Bogoslovlag. Victor Dizendorf, a researcher of the labor army, using the example of Usollag's archive data, gives more detailed data on mortality and concludes that the first batches of the hard-mobilized suffered the greatest losses: out of 4945 people who arrived in this camp first, 2176 - 44% died.

The same Dizendorf in his article “To remember: labor army, forest camps, Usollag” drew attention to cases of conviction and sending labor-mobilized to ordinary correctional camps and GULAG prisons: “Labor army and" ordinary "GULAG were, I would say, these communicating vessels “- notes the researcher. He also mentions the order of the NKVD and the Prosecutor's Office of the USSR of April 29, 1942, according to which the Germans who had served their punishment were ordered instead of being released from the camp to be transferred to "working columns".

According to the historian Zemskov, if in 1939 there were 18,500 Germans in prison camps in GULAG, then in 1945 it was 22,500. As a percentage of the total number of prisoners, this meant a twofold increase (from 1.4% to 3.1%). Among them were those who were convicted as a spy before the war, and those who ended up in camps for dissatisfaction with deportation policies, and who tried to desert from the labor army. Thousands of army trudmobilizovannyh on paper to prisoners did not apply.

Without the right to rehabilitation

Gerhard Voltaire recalls how, after a break in the Great Patriotic War, there were changes in the labor army: “Our life and work in 1944 changed a lot. Now no one was dying of hunger, and the "goners" gradually "went out into people." They externally transformed. We were dressed in the old Red Army uniform, taken from the wounded, washed, with patches in the field of bullet holes, often with remnants of blood stains. With traces of carefully knitted buttonholes on gymnasts and jackets, asterisks on hats. But there is still anxiety to everyone and always. Despite the kilos of bread that was given to those who were busy at the logging site, and for improved welding. And at the beginning of 1944, there was even a semblance of meat in our diet - “failures”. ”

After the victory of the Red Army, the Germans, of course, hoped for demobilization, but it did not happen. Only in March 1946, the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR ordered the disbanding of the labor columns of the labor-mobilized and liquidate zones. However, after that, all former labor soldiers had no right to go to the places of residence of families, but received the status of special settlers and continued to work on the same construction sites and enterprises. Disabled people, women over 45 and men over 55, as well as mothers of young children, could return to the places of residence of families (to those places of expulsion in Kazakhstan and Siberia). Those who were left in a special settlement at the site of the former zones of the labor army were allowed to call families to their homes.

On November 26, 1948, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a top secret decree on criminal responsibility for escaping from places of compulsory and permanent settlement of persons evicted to remote areas of the Soviet Union during the Patriotic War. It was reported that Germans, Chechens, Ingushs, Crimean Tatars and other peoples deported in 1941–42 were relocated to remote areas of the USSR "forever, without the right to return them to their former places of residence." For trying to leave the place of special settlement, it was supposed to be 20 years of hard labor, and for complicity in the organization of escape, five years in prison.

In the early 1950s, the number of Germans living in special settlements only increased: repatriates were exiled from territories occupied in the past, "fixed" in Siberia and in the Urals those who lived there for many generations. By January 1, 1953, more than 1 million 200 thousand Germans were special settlers.

All restrictions on German special settlers were lifted only by December 1955, the liberation was carried out in several stages. The Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR stated that “the lifting of restrictions on special settlement from the Germans does not entail the return of property confiscated during eviction,” and it was also prohibited for them to return to the places from which they were evicted.

In 1991, he wrote in his book Gerhard Voltaire, who had passed through five years of labor to the Germans, it was decided to award the rear workers with medals depicting Stalin's profile. The author reports that he, like many of the Labor Army soldiers who lived before this event, refused the award.

-

Elena Shmaraeva, published in the Mediazon edition

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Comments

Post a Comment